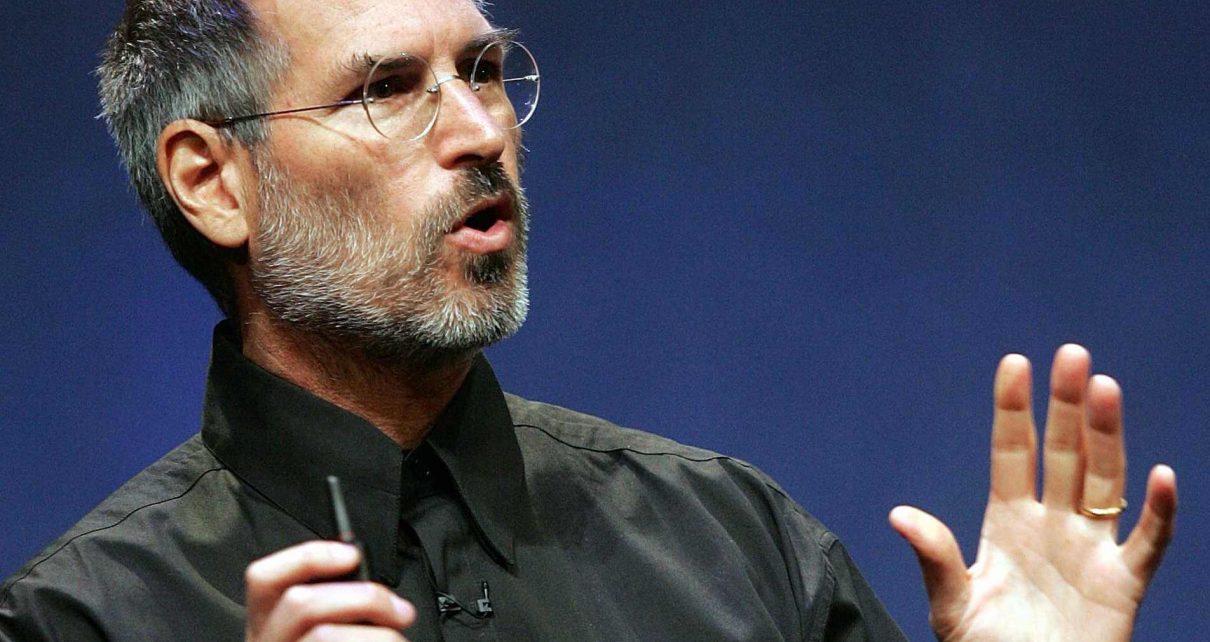

Steve Jobs’ vision of a “computer for the rest of us” sparked the PC revolution and made Apple an icon of American business. But somewhere along the way, Jobs’ vision got clouded — some say by his ego — and he was ousted from the company he helped found. Few will disagree that Jobs did indeed impede Apple’s growth, yet without him, the company lost its sense of direction and pioneering spirit. After nearly 10 years of plummeting sales, Apple turned to its visionary founder for help, and a little older and wiser Jobs engineered one of the most amazing turnarounds of the 20th century.

The adopted son of a Mountain View, Calif., machinist, Steve Jobs showed an early interest in electronics and gadgetry. While in high school, he boldly called Hewlett-Packard co-founder and president William Hewlett to ask for parts for a school project. Impressed by Jobs, Hewlett not only gave him the parts, but also offered him a summer internship at Hewlett-Packard. It was there that Jobs met and befriended Steve Wozniak, a young engineer five years his senior with a penchant for tinkering.

After graduating from high school, Jobs enrolled in Reed College in Portland, Ore. but dropped out after one semester. He had become fascinated by Eastern spiritualism and took a part-time job designing video games for Atari in order to finance a trip to India to study Eastern culture and religion.

Related: Steve Jobs: An Extraordinary Career

When Jobs returned to the U.S., he renewed his friendship with Wozniak, who had been trying to build a small computer. To Wozniak, it was just a hobby, but the visionary Jobs grasped the marketing potential of such a device and convinced Wozniak to go into business with him. In 1975, the 20-year-old Jobs and Wozniak set up shop in Jobs’ parents’ garage, dubbed the venture Apple, and began working on the prototype of the Apple I. To generate the $1,350 in capital they used to start Apple, Steve Jobs sold his Volkswagen microbus, and Steve Wozniak sold his Hewlett-Packard calculator.

Although the Apple I sold mainly to hobbyists, it generated enough cash to enable Jobs and Wozniak to improve and refine their design. In 1977, they introduced the Apple II — the first personal computer with color graphics and a keyboard. Designed for beginners the user-friendly Apple II was a tremendous success, ushering in the era of the personal computer. First-year sales topped $3 million. Two years later, sales ballooned to $200 million.

But by 1980, Apple’s shine was starting to wear off. Increased competition combined with less than stellar sales of the Apple III and its follow-up, the LISA, caused the company to lose nearly half its market to IBM. Faced with declining sales, Jobs introduced the Apple Macintosh in 1984. The first personal computer to feature a graphical-user interface controlled by a mouse, the Macintosh was a true breakthrough in terms of ease-of-use. But the marketing behind it was flawed. Jobs had envisioned the Mac as a home computer, but at $2,495, it was too expensive for the consumer market. When consumer sales failed to reach projections, Jobs tried pitching the Mac as a business computer. But with little memory, no hard drive and no networking capabilities, the Mac had almost none of the features corporate America wanted.

For Jobs, this turn of events spelled serious trouble. He clashed with Apple’s board of directors and, in 1983, was ousted from the board by CEO John Sculley, whom Jobs had handpicked to help him run Apple. Stripped of all power and control, Jobs eventually sold his shares of Apple stock and resigned in 1985.

Related: As Steve Jobs Once Said, ‘People With Passion Can Change The World’

Later that year, using a portion of the money from the stock sale, Jobs launched NeXT Computer Co., with the goal of building a breakthrough computer that would revolutionize research and higher education. Introduced in 1988, the NeXT computer boasted a host of innovations, including notably fast processing speeds, exceptional graphics and an optical disk drive. But priced at $9,950, the NeXT was too expensive to attract enough sales to keep the company afloat. Undeterred, Jobs switched the company’s focus from hardware to software. He also began paying more attention to his other business, Pixar Animation Studios, which he had purchased from George Lucas in 1986.

After cutting a three-picture deal with Disney, Jobs set out to create the first ever computer-animated feature film. Four years in the making, “Toy Story” was a certified smash hit when it was released in November 1995. Fueled by this success, Jobs took Pixar public in 1996, and by the end of the first day of trading, his 80 percent share of the company was worth $1 billion. After nearly 10 years of struggling, Jobs had finally hit it big. But the best was yet to come.

Within days of Pixar’s arrival on the stock market, Apple bought NeXT for $400 million and re-appointed Jobs to Apple’s board of directors as an advisor to Apple chairman and CEO Gilbert F. Amelio. It was an act of desperation on Apple’s part. Because they had failed to develop a next-generation Macintosh operating system, the firm’s share of the PC market had dropped to just 5.3 percent, and they hoped that Jobs could help turn the company around.

At the end of March 1997, Apple announced a quarterly loss of $708 million. Three months later, Amelio resigned and Jobs took over as interim CEO. Once again in charge of Apple, Jobs struck a deal with Microsoft to help ensure Apple’s survival. Under the arrangement, Microsoft invested $150 million for a nonvoting minority stake in Apple, and the companies agreed to “cooperate on several sales and technology fronts.” Next, Jobs installed the G3 PowerPC microprocessor in all Apple computers, making them faster than competing Pentium PCs. He also spearheaded the development of the iMac, a new line of affordable home desktops, which debuted in August 1998 to rave reviews. Under Jobs’ guidance, Apple quickly returned to profitability, and by the end of 1998, boasted sales of $5.9 billion.

Against all odds, Steve Jobs pulled the company he founded and loved back from the brink. Apple once again was healthy and churning out the kind of breakthrough products that made the Apple name synonymous with innovation.

But Apple’s innovations were just getting started. Over the next decade, the company rolled out a series of revolutionary products, including the iPod portable digital audio player in 2001, an online marketplace called the Apple iTunes Store in 2003, the iPhone handset in 2007 and the iPad tablet computer in 2010. The design and functionality of these devices resonated with users worldwide.

Related: 10 Must-Read Inspiring Biographies of Business Leaders

Despite his professional successes, Jobs struggled with health issues. In mid-2004, he announced in an email to Apple employees that he had undergone an operation to remove a cancerous tumor from his pancreas. In January 2011, following a liver transplant, Jobs said he was taking a medical leave of absence from Apple but said he’d continue as CEO and “be involved in major strategic decisions for the company.”

Eight months later, on August 24, Apple’s board of directors announced that Jobs had resigned as CEO and that he would be replaced by COO Tim Cook. Jobs said he would remain with the company as chairman.

“I have always said if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple’s CEO, I would be the first to let you know,” Jobs said in a letter announcing his resignation. “Unfortunately, that day has come.”

In October 2011, Jobs passed away at the age of 56 due to complications related to pancreatic cancer. Jobs once described himself as a “hopeless romantic” who just wanted to make a difference. Quite appropriately like the archetypal romantic hero who reaches for greatness but fails, only to find wisdom and maturity in exile, an older, wiser Steve Jobs returned triumphant to save his kingdom.